Unpacking SA's homeless crisis | How socio-economic factors fuel the TB crisis among the homeless

South Africa has some of the highest uberculosis (TB) numbers in the world.

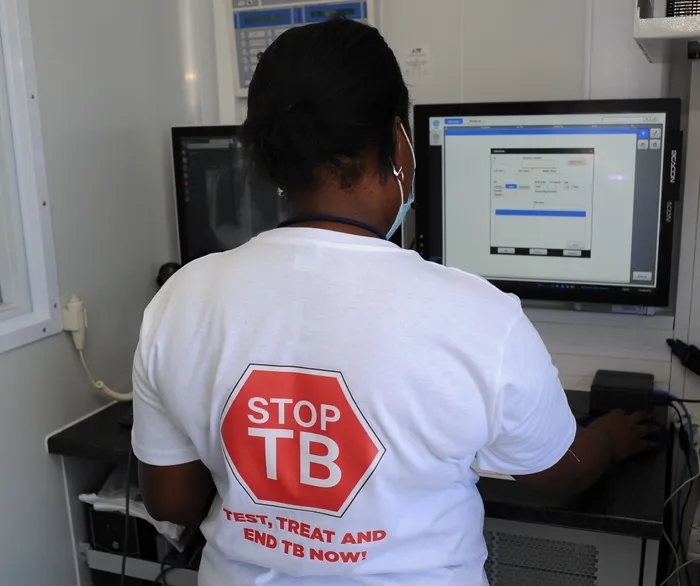

Image: Henk Kruger/ Independent Newspapers

Socio-economic factors such as housing, malnutrition and drug abuse are definitely one of the leading factors when it comes to South Africa’s high tuberculosis (TB) numbers.

The country has an incidence rate of 468 per 100,000 people. In 2022, authorities recorded an estimated 54,000 deaths from TB, which was co-driven by the high HIV infection rate.

TB and HIV go hand-in-hand, with HIV compromising the immune system allowing TB to attack the body, and specifically the lungs.

The homeless are some of the most vulnerable people when it comes to TB.

Dr Jacques Cronje, medical manager of Sonstraal TB hospital in Paarl, says homeless people don’t make up a lot of their patients, but are the people most prone to end up at the hospital with a TB related illness.

“TB is a big problem in the Western Cape and in the country,” Cronje told IOL.

“When it comes to the homeless, people who stay under a bridge or a shelter made from cardboard … they are in the system throughout the year.

“TB is an illness commonly found in people whose immune systems are compromised. And the homeless are normally malnourished, while HIV and drugs also play a massive role in people contracting it.”

According to Cronje, there are different types of homeless people that they treat at the hospital. Some are discarded by their families after contracting the disease, while others simply just stay on the street.

But the biggest challenge to treat these patients in hospital is to get them in a routine, for them to eat, take their pills and educate them about the disease itself.

Patients not completing their TB medication are probably the biggest headache healthcare practitioners at TB facilities are facing.. It becomes a vicious cycle, because patients who default almost always come back to the hospital … or worse.

“The biggest challenge in TB treatment is the completion of the medication. One thing that we can definitely say is that if you drink your pills, the chances of you getting better is very good,” Cronje said.

“Not a lot of people understand that feeling better doesn’t mean you're cured. TB has this characteristic when it goes into a dormant phase in the lungs. If you stop your medication before those dormant germs aren’t eradicated, then you will be back to square one.

“To get a homeless person to get their pills at the clinics and do follow-up tests remains a problem. We see factors such as people rebelling against the treatment, while a lack of education about what they need to continue to do to get better is another major factor.

“Guidance rests on the shoulders of the doctors and the nursing staff to bring the message through, because it's a strange concept to explain to people - something that is making you sick that you can’t see.”

However, discharging a patient who lives on the streets and end up with little function after contracting TB is one of the great ethical dilemmas that the staff at Sonstraal Hospital and indeed other hospitals around the country face.

For starters, the patients are given shelter, food and physiotherapy. They see a social worker who sorts out their social grants, keeps in contact with loved ones and have nurses who give their medicine on time.

But on the streets it's a fight for survival, especially if your lungs are no longer functioning properly and you can’t walk far or have to make use of a wheelchair.

“People in a TB hospital get more food than in a normal hospital, because they have lost so much weight. We get people who gain 15kg in a few months just by staying in hospital,” Cronje said.

“Now we get to some of our difficult ethical dilemmas. TB is a destructive and deadly illness. People who are treated early enough and take medicine diligently will almost always get better. But if you leave TB untreated it can cause grave harm and the odds of living the same life, especially out on the streets, are really bad.

“Imagine being homeless and having to get around in a wheelchair, because you can’t walk. So it’s difficult to discharge people who find themselves in that state, who can’t look after themselves on the street.

“The medical staff and social workers struggle with that, because there are no safe havens for those people. It’s difficult for us to just discharge a patient because of the uncertainty about them actually coping and getting better.

“Unfortunately it’s the reality of the situation. There is always someone else who needs care when someone gets better.”

But, according to Cronje, most homeless people actually prefer to get back on the streets, because they can be free to do what they want to. There are no rules on the streets, about when to eat, when to sleep. They can come and go as they please … and many are happy with that.

“Most people who live on the street want to get back to the street, because there are no rules on the streets and they can come and go and do whatever they please.

“It’s sad, and you can try and help people. But at the end of the day it’s their choice and you have to respect it.

@JohnGoliath82

IOL

Related Topics: