Who does and who doesn't meet the 'Afrikaner' criteria for Trump's resettlement offer?

The South African delegation led by President Cyril Ramaphosa with the US delegation and President Donald Trump at the White House.

Image: GCIS

With the second batch of white Afrikaners having quietly arrived in the United States last week, as part of President Donald Trump’s offer to resettle them amidst false claims of white genocide and persecution in South Africa, a discussion has been raised around who exactly can meet the criteria.

The second batch is part of a larger group that applied to be resettled within the US, according to the Head of Public Relations for trade union Solidarity, Jaco Kleynhans.

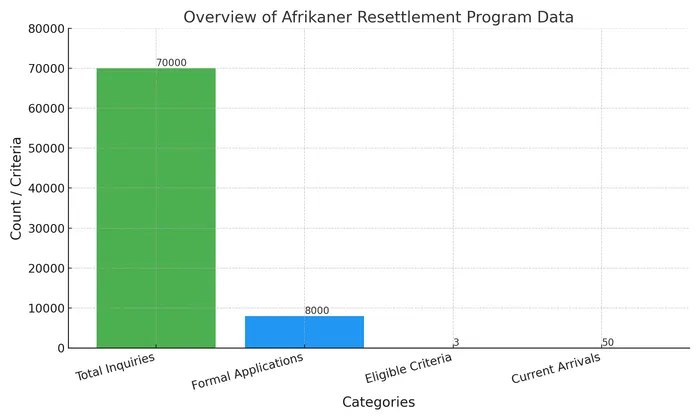

Kleynhans further shared that there have been 70,000 enquiries and so far there have been about 8,000 formal applications.

“How many people will be resettled will be determined by many factors – how many people apply in future, (and) how many applications are successful?”

Explaining their role in the process, Kleynhans said: “We are not involved at all. We only help people with enquiries and refer them to the right people at the embassy.”

A US Mission to South Africa spokesperson said: “The U.S. Embassy in Pretoria continues to review inquiries from individuals who have expressed interest to the Embassy in resettling to the United States and is reaching out to eligible individuals for refugee interviews and processing.”

“Refugees continue to arrive in the United States from South Africa on commercial flights as part of the Afrikaner resettlement program’s ongoing operations.”

In their records, the spokesperson said they have received almost 50,000 inquiries regarding refugee resettlement to the United States from South Africa.

Afrikaners waiting to be briefed by US government officials in a hangar at Dulles International Airport, Washington on May 12, 2025.

Image: AFP

According to the criteria, to be eligible for US resettlement consideration (USRAP), individuals must meet all of the following criteria:

- Must be of South African nationality; and

- Must be of Afrikaner ethnicity or be a member of a racial minority in South Africa; and

- Must be able to articulate a past experience of persecution or fear of future persecution.

In his IOL opinion piece this week, Clyde N.S. Ramalaine argued that the criteria used, has opened an unexpected opportunity to examine how it could inadvertently apply to other historically marginalised South African groups, “particularly the KhoeSan and Coloured communities”.

“The original purpose of the USRAP criteria appears to have been the protection of white South Africans fearing political and land displacement. However, its language is broad enough to permit reinterpretation.

“A literal application of its three criteria—nationality, minority status, and persecution—clearly allows for KhoeSan and Coloured inclusion,” Ramalaine said.

Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB) CEO, Lance Schultz, explained that the word "Afrikaner" derives from the Dutch word Afrikaan, meaning "African," combined with the suffix -er, which denotes a person associated with a place or characteristic.

“Thus, ‘Afrikaner’ literally means ‘one from Africa’ or ‘African’ in Dutch.”

Schultz explained that initially, "Afrikaner" was a broad term that could apply to anyone born in Africa, including people of mixed descent or even enslaved individuals, but over time, it became more narrowly associated with the white, Dutch-speaking settler population who developed a distinct cultural and linguistic identity separate from their European origins.

“Many views or schools of thought may exist regarding the historical origin of the word ‘Afrikaner’; two of these can be explored. Firstly, the term ‘Afrikaner’ is regarded as having its roots in the Dutch colonial history of South Africa, and it refers to white Afrikaans-speaking persons.

“The term was initially used to describe people of European descent, primarily Dutch, who settled in southern Africa and identified with the continent as their home. This reflects the complex interplay of language, culture, and identity in the region,” Schultz said.

He explained that the term "Afrikaner" has undergone significant changes in meaning, usage, and connotation since its emergence in the 17th century, reflecting shifts in historical, social, and political contexts in South Africa.

“After the end of apartheid in 1994, the term ‘Afrikaner’ became more contested. It remains primarily associated with white, Afrikaans-speaking South Africans, but is increasingly debated in terms of inclusivity. Some advocate for a broader definition that includes all Afrikaans speakers, regardless of race, such as Coloured and Black Afrikaans-speaking communities,” Schultz said.

“The legacy of apartheid has made ‘Afrikaner’ a polarising term for some, associated with historical oppression, while others view it as a cultural or linguistic identity divorced from political connotations. In modern South Africa, Afrikaner identity is diverse, with some embracing globalised or progressive values and others holding onto conservative or nationalist sentiments.”

Head of Public Relations for trade union Solidarity, Jaco Kleynhans said that there have been 70,000 enquiries about US President Donald Trump's resettlement offer and so far there have been about 8,000 formal applications.

Image: Graphic

He explained that the categorising of who does and doesn’t count as part of a specific ethnic group, such as "Afrikaner" in the context of Trump’s 2025 executive order, involves navigating complex linguistic, cultural, and political terrain.

“This policy has spotlighted the term ‘Afrikaner’ and raised questions about its definition, revealing language pitfalls that can lead to exclusion, misrepresentation, or manipulation of ethnic identity.”

He added that ethnic categories like "Afrikaner" often blend linguistic, cultural, ancestral, and racial elements, but vague or inconsistent definitions can lead to misinterpretation or exclusion.

“The executive order appears to define ‘Afrikaner’ narrowly as white, Afrikaans-speaking South Africans, aligning with historical apartheid-era usage that excluded non-white Afrikaans speakers, such as the Coloured community, who form a significant portion of Afrikaans speakers. This exclusionary framing ignores the linguistic diversity of Afrikaans speakers and reinforces a racialised interpretation of the term.”

Director at the Centre for Education Rights and Transformation from the University of Johannesburg, Professor June Bam-Hutchison, added that the Trump administration is instrumentalising an apartheid white racist notion of ‘Afrikaner’ as “embedded within Afrikaner nationalism which mutated into the ethnic foundations of the ‘chosen people’ (white Afrikaners)”.

“Of course, indigenous people and Africans have never been at the heart of Trump’s interests. Since 1994, we have embraced a South African inclusivity, rejecting ‘Colouredism’ as it has a nasty Apartheid history of imposed dislocation from Africa.

“It would be foolish to believe that Trump’s presidency, in this gesture from its embassy, includes indigenous people from anywhere in the world, although opportunistic ethnic nationalists would want to claim refugee status to further Apartheid ideals of divide and rule. Such claims are questionable within this context,” Bam-Hutchison said.

Bam-Hutchison said Trump’s actions are about entrenching global white supremacy, and the strategic positioning politically and economically on the continent.

“Should ‘Coloureds’ claim refugee status on the grounds stated, it would be merely opportunistic in a country which brutally dispossessed the Native American people and in which the Black Lives Matter movement has major unsettled business with the Trump administration.

“Definitely, a highly suspicious gesture peppered with significant and glaring contradictions for the world to see at a time of live genocide in Gaza,” Bam-Hutchison said.

When asked if even people from the Cape Flats, who see themselves as “Afrikaners”, could also apply, Kleynhans said, “Yes”.

“The entire process has been discredited by many in the mainstream media, as well as in the South African government. We find this despicable. The US government has the right to offer refugee status to anyone they wish.

“Furthermore, many Afrikaners experience serious discrimination and persecution. Many Afrikaners feel completely alienated from the country they love so much. This is a tragedy. Furthermore, our main focus as Solidarity has always been and is to ensure that Afrikaners can remain in South Africa,” Kleynhans said.

“We do not want Afrikaners to feel that they have lost all hope for a future in South Africa. We will therefore continue to fight for a future for Afrikaners in South Africa.”

Head of Public Relations for trade union Solidarity, Jaco Kleynhans said that there have been 70,000 enquiries, so far there have been about 8,000 formal applications.

Image: Graphic

Schultz added that PanSALB views the distinction between Afrikaner nationalism and the broader use of Afrikaans among diverse linguistic groups in South Africa as critical to understanding the country’s complex social, cultural, and political landscape.

“Afrikaner nationalism historically refers to the ethno-nationalist ideology of white, Afrikaans-speaking South Africans, particularly tied to apartheid and earlier Boer resistance to British rule.”

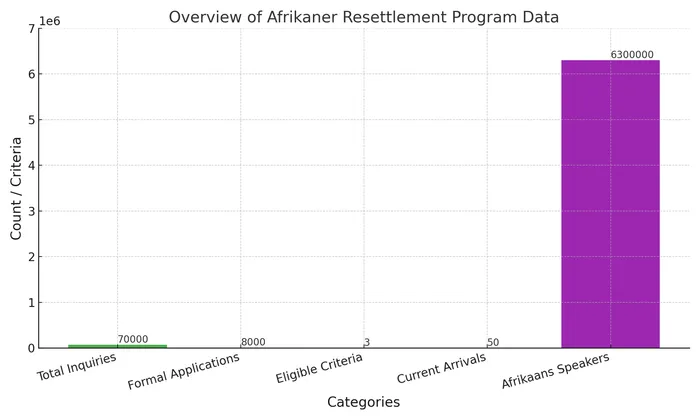

He explained that Afrikaans is a language spoken by diverse groups, including white Afrikaners, Coloured communities, Black South Africans, and others, with over 6,3 million speakers according to the 2022 Census by Stats SA, representing 10.6% of the country's population.

“Failing to address this distinction, particularly in light of recent events like the 2025 Trump executive order emphasising ‘ethnic minority Afrikaners’ could have profound implications for South Africa’s social cohesion, linguistic equity, and political stability.”

theolin.tembo@inl.co.za