How African Soldiers Shaped the Outcome of WWII

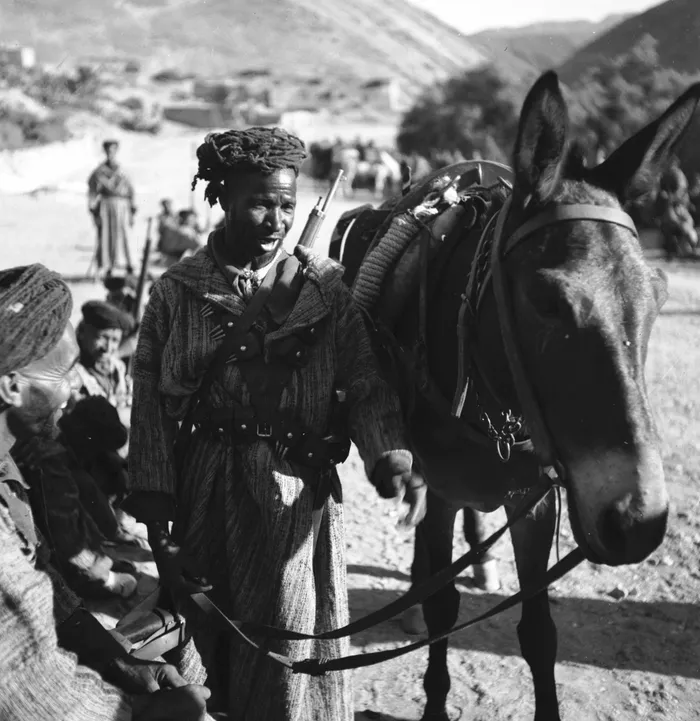

A Moroccan soldier in the French army in 1945. When the war was finally over, the veterans were demobilized. White soldiers came home in a blaze of glory – commended with medals and received with triumph. For Africans, the reception was otherwise, says the writer.

Image: AFP

F. Andrew Wolf, Jr.

Its tumult ended more than 80 years ago, however, the Second World War must always be remembered, as should the African soldiers whose contribution and sacrifice laid the groundwork for an independent Africa.

From a Western perspective, Africa lies somewhere at the periphery of its history in relation to WWII. The accepted war narrative of the West focuses primarily on the European and Pacific theatres. But such a rendering is quite misleading.

Over a million Africans took part in the war, in every capacity, as combatants or otherwise. Africans were substantively involved in every major theatre of the war: Africa, Europe, the Middle East, India, and Myanmar (Burma). Many would never return home. Moreover, unlike their European comrades in service, their sacrifices have rarely been acknowledged.

Colonial Africa

When World War II started, Africa was (with few exceptions) a patchwork of colonies. A third of the continent’s expanse (just over 10 million square kilometres) was governed by the British Empire (as colonies or dependent territories) rendering it by default on the side of the Allies.

France was second in land holdings with almost 9 million square kilometres (encompassing West and Central Africa, and Madagascar). In 1940 over half of France was occupied by German forces, while the remaining portion was under the Vichy collaborationist government. Yet, most colonies proclaimed their allegiance to Charles de Gaulle’s Free France government in exile.

The colonial powers were faced with a severe shortage of manpower; hence, Africans were pressed into service. African soldiers performed a variety of tasks: they fought in infantry units, transported munitions and provisions to the front lines helped save wounded (often under fire), built bases, airfields, and roads and helped guard them.

Soldiers for Britain

In West Africa, Britain began to expand its Royal West African Frontier Force (RWAFF) – from a small number of 18,000 men in 1939, it grew to 150,000 by 1945, producing 28 battalions and two divisions that saw service in East Africa and the Far East.

In British East Africa, the King’s African Rifles Regiment (KAR) served as the nucleus for the soon-to-be-formed African units and detachments. The KAR, akin to its Western counterpart the RWAFF, created a vast array of forces during WWII: over 40 infantry battalions. Officers were Europeans (from the Royal Army), while the rank-and-file NCOs were Africans from Tanganyika (Tanzania), Kenya, Uganda and Nyasaland (Malawi).

East Africa campaign

In 1940-1941, African soldiers played a pivotal role in East Africa – the liberation of the Horn of Africa countries from Fascist Italian occupation. African soldiers from East and West Africa were fighting alongside others from the Union of South Africa, Britain, India, Australia and New Zealand.

The campaign was a critical victory: Italian forces were either destroyed or surrendered en masse with the liberation of Somaliland, Ethiopia and Eritrea – a devastating blow to Mussolini’s pride and military.

Rhodesian contribution

The contribution from the southern part of Africa to the Allied war effort deserves particular mention. Two countries provided more than their fair share of servicemen for the cause – Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and the Union of South Africa.

During WWII, Rhodesia, as a percentage of its population, provided more soldiers (black and white) than any other country in the empire, including Britain itself.

White Army

In South Africa, the policy of apartheid was yet to be introduced officially, but it was ‘de facto law.’ The state policy was strict: there was to be a white army only. No black African could be enlisted as a combat soldier. But the government was faced with a serious problem.

There was no mandatory military service in the country and the Union Defense Force (as the South African Army was called then) was volunteer and small. Moreover, Die Afrikaner Volk (a white population of Dutch, French and German ancestry) was strongly opposed to war with Germany and few joined the UDF.

Facing severe shortages, the government permitted the enlistment of the Coloreds (the official term for those of mixed lineage) and the Indians. They were initially inducted as drivers and engineers – later tasked as dispatchers, medics, clerks and eventually guards.

South Africans fought with distinction. Of 330,000 South Africans who saw service in WWII, 77,000 were black.

Senegalese Riflemen

One must not focus the story entirely on British subjects. France had a corps of colonial infantry – the Senegalese Tirailleurs (Senegalese Riflemen).

After France’s fall, Senegalese Tirailleurs fought tenaciously. Their major campaign was none other than the liberation of France with the French 1st Army. They conquered Elba and then landed in southern France, fighting their way northward to Alsace.

At war’s end

When the war was finally over, the veterans were demobilized. White soldiers came home in a blaze of glory – commended with medals and received with triumph. For Africans, the reception was otherwise. The British barely bothered to honour either their contribution or their heroism – the single exception being the 1946 Victory Parade in London. As for the French and Belgians – they were content to let their “soldats-noirs" go with meagre pensions and few words of comfort or gratitude.

Upon their return, many of them found themselves out of work and their lives still controlled by Europeans. There was a general feeling of disillusionment, for they believed that colonial powers owed them more for the sacrifices they endured. From this consciousness, the initial feelings of dissent were born.

Consciousness-raising

The African people started to reassess their racial views. Before the war Europeans were considered different from other people. During the war, Africans came to realize that there was nothing special or different about them. The myth of European invulnerability was no more.

Political consciousness was awakened. Many Africans learned to read and write while in the ranks and newspapers were everywhere. They knew now how affairs in foreign lands could affect their own lives. They asked:

If it was wrong for the Germans to rule the French, why is it acceptable for Europeans to rule Africans?

The realm of politics had shifted worldwide when the war was over. Perspectives on colonialism were transforming on the global stage, and these fresh views worked against European colonial powers.

Over a million Africans who were called to service by colonial powers took part in the war. Many never returned – and those who did were little recognized for their sacrifice.

But independence was already in the air in Africa and equally awakened in the hearts of its people.

* F. Andrew Wolf, Jr is director of The Fulcrum Institute, an organization of current and former scholars, which engages in research and commentary, focusing on political and cultural issues on both sides of the Atlantic.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.