Justice delayed: Luthuli, Mxenge families quest for the truth

FREEDOM MONTH

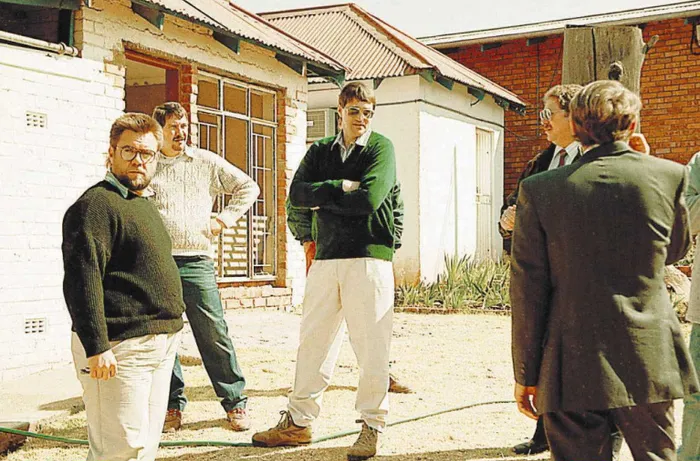

Eugene de Kock (C), head of the apartheid-era police death squads, at his Vlakplaas headquarters where activists were tortured and murdered in the 1980's. Why did South Africa’s post-apartheid government wait for thirty one years to get justice for activists who gave us the freedom we are enjoying today?, asks the writer.

Image: AFP

Prof. Bheki Mngomezulu

THERE have been mixed reactions to the re-opening of Chief Albert Luthuli and Griffiths Mlungisi Mxenge’s inquest.

On Monday 14 April 2025, the High Court in Pietermaritzburg listened to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) which promised to present new evidence that will necessitate that the previous finding on this matter which dismissed any wrongdoing by anyone be overturned.

Parallel to this inquest is another one concerning Griffiths Mxenge, a human rights lawyer, who was stabbed to death in uMlazi Township South of Durban. He brutally lost his life at the hands of the apartheid death squad which was led by Dirk Coetzee. Mxenge was stabbed 45 times. To make matters worse, his throat was cut.

The Mxenge matter was postponed to 17 June 2025. This postponement was occasioned by the South African Police Service’s (SAPS) request that those implicated in this case be granted financial resources to pay for their legal representation. The request was premised on the fact that the accused were working for the then South African police department at the time.

Both leaders had a reputable history. Luthuli was elected to lead the ANC during critical times in 1952 following the adoption of segregation as a government policy called apartheid. His contribution saw him being the first South African to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1960 for spearheading the fight against apartheid. The other three South Africans to win this prize [Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 1984, and Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk in 1993] joined him years later.

Sadly, on 21 July 1967, Luthuli died under very mysterious circumstances, which have necessitated this inquest.

Officials claimed that Luthuli could hardly see or hear. Ironically, on that fateful day, he went to have a meeting with his store manager before proceeding to his field. Two questions arise. The first one is how did he find his way to the shop and subsequently to the farm if he could not see? Secondly, how did he convene a meeting with his store manager if he could not hear? The two questions were amplified by the fact that Luthuli’s injuries were inconsistent with the so-called goods train accident.

On the other hand, Mxenge was a well-known lawyer who represented the victims of the Matola raid in Mozambique and those of the Lesotho raid. Like Luthuli, he was aligned to the ANC. By default, he was dubbed the ‘enemy’ of the apartheid state.

Because their deaths left many questions unanswered, their families have always wanted to get those answers so that they could close this chapter.

Section 17A (1) of the Inquest Act 58 of 1959 stipulates that the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development may request a judge president of a provincial division of the Supreme Court to designate any judge of the Supreme Court of South Africa to re-open the inquest. This is how we got to where we are.

Now, the main question arises: should we celebrate this inquest?

The answer to this question depends on the point of emphasis. Responding to this question, Sandile Luthuli the grandson of Chief Luthuli focused on finding closure. He stated that the family hoped to find closure on two levels - first on how Chief Luthuli really died and secondly, who should be held criminally liable for his death.

Albert Mthunzi Luthuli, another one of Chief Luthuli’s grandchildren focused on punishing the perpetrators. He was less excited, arguing that it was years after the deaths of "many people that we suspected of being involved in my grandfather's murder." For Albert, while the inquest is a welcome development, justice will not be served if any form of punishment is meted out posthumously.

Another lens through which this inquest could be viewed is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Albert lamented that the TRC did not live up to its expectations. He averred that "We believe the TRC […] let many families of victims down by giving amnesty to apartheid murderers." Such statements implicitly remind South Africans that the TRC missed the boat, thereby contributing to some of the incessant pain many apartheid victims are still dealing with decades after the end of apartheid.

On the Mxenge matter, Butana Almond Nofomela who was a member of the covert hit-squad confessed to killing Mxenge and other ANC members. Intriguingly, he, together with Dirk Coetzee and David Tshikalange were found guilty in 1997 of Mxenge's murder but were granted amnesty by the TRC. This happened before the criminal case could be concluded.

The saying ‘justice delayed is justice denied’ fits neatly in these two matters. The fact that these events happened in 1967 and 1981 respectively means that some of the culprits might no longer be alive to account for their sins. Secondly, some of the details about these cases might not come to light. In the process, the families of these two activists will never heal completely due to unanswered questions.

The question arises: Why did South Africa’s post-apartheid government wait for thirty years to get justice for the activists who gave us the freedom we are enjoying today? Where was the NPA for the past thirty years? While this inquest is a welcome move by the NPA, it is an indictment on both the NPA and the ANC which knew about these and many other cases but did nothing to get justice to the bereaved families.

Looking at all the issues discussed above, one wonders what were the details of the sunset clauses which served as a precursor to the 1994 new political dispensation. Did the incoming black administration over-compromise to ascend to power? If so, what about those who paid the ultimate price for us to achieve the freedom we are enjoying today? Does our injustice to their families amount to our gratitude to them? I don’t think so.

In a nutshell, the crux of my argument is that there is little to celebrate about this inquest.

* PROF BHEKI MNGOMEZULU Director of the Centre for theAdvancement of Non-Racialismand Democracy at the NelsonMandela University