The erosion of moral values in South African political movements

Opinion

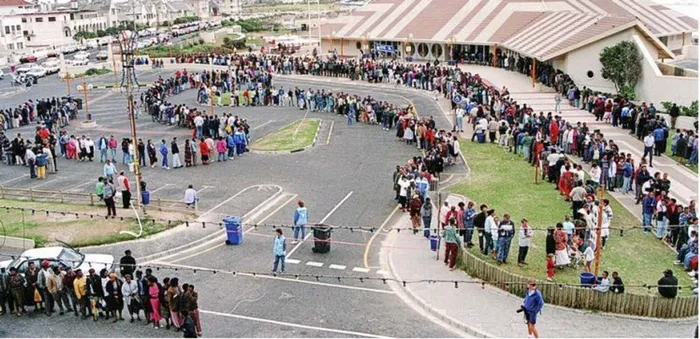

There were snaking queues of South Africans eager to vote in a new government during the first democratic election in 1994. But hope for a better future has become overshadowed by corruption and allegations of state capture.

Image: African News Agency (ANA) Archives

“What I fear is that the liberators emerge as elitists who drive around in Mercedes Benzes and use the resources of this country to live in palaces and to gather riches.” — Chris Hani

THERE is a saying in various circles, often spoken in whispers, that there is a moral difference between Inkatha and the IFP. The two carry vastly different connotations.

Pre-1994, Inkatha Yenkululeko Yesizwe was a movement of voluntary activists — men and women driven by love and passion for liberation, not personal gain. Contrast this with the post-1994 IFP, a political party whose activists are, to some extent, motivated by “What’s in it for me?” — Ngizotholani.

The same troubling shift applies to the ANC. The pre-1994 ANC was a movement of selfless revolutionaries, individuals who sacrificed careers, freedom, and even their lives for the emancipation of our people. Today’s ANC, however, is glaringly consumed by greed, its moral compass shattered.

The veterans of both movements decry this inversion of values, where the struggle’s principled disdain for wealth accumulation has been replaced by a merciless contest in conspicuous consumption. This is an era where narrow self-interest trumps the collective good — something the late Dr Margaret Mncadi of the ANC and the living stalwart Abbey Mchunu of the IFP would have condemned in the strongest terms.

At the risk of undermining the work of contemporary women, one cannot help but contrast the women of the struggle era with those of today. Where has the resilience, tenacity, and assertiveness of the 1950s women gone? What happened to the visionary leadership of the Mncadis, Ngoyis, and Josephs — women who fought for the upliftment of others rather than personal enrichment?

Today’s women risk undoing the hard-won gains of their predecessors. The struggle for gender equality has been reduced to a scramble for positions and tenders, rather than a sustained fight for systemic change.

The women of the 1950s understood that liberation was not about individual advancement but collective emancipation. Sadly, many of today’s female leaders seem preoccupied with their own “personal RDP”, a far cry from the selflessness that once defined our movement.

The ANC and IFP are not just political parties; they are moral influencers. The conduct of their leaders shapes the values of the younger generation. Yet, how can we ignore the spine-chilling headlines of corruption, fraud, and scandal involving their members?

The period between the 1940s and the late 1980s was defined by sacrifice. Figures such as Mandela, Gwala, and Sobukwe endured imprisonment, torture, and exile in their fight against apartheid.

Many of these leaders were highly educated — they could have pursued comfortable careers but chose instead to wage a struggle for justice. The 1970s to early 1990s saw an even greater resolve, with thousands of cadres joining MK and Poqo, making the country ungovernable despite brutal states of emergency.

Post-1994, however, the struggle’s ethos was abandoned. Politics became a scramble for material benefits — what Michela Wrong aptly termed “our turn to eat”. Many who joined after the unbanning of political parties lacked the ideological grounding of earlier generations. Their political baptism came not from the trenches of resistance but from the opportunism of a new democratic dispensation.

Machiavelli observed that in politics, as in medicine, early symptoms of decay are hard to detect but easy to cure; left unchecked, they become obvious but incurable. Clausewitz, meanwhile, saw politics as a contest for power and resources, not governance itself. This explains the factional wars tearing apart the ANC and, to a lesser extent, the IFP.

At the heart of these divisions is a battle for control, not of ideas, but of state resources. Reinhold Niebuhr warned that politics would always be where conscience clashes with power. Today, money has eroded conscience. As Teresa Nesbit Cosby noted: “Money, politics, and influence are like water to the river, they belong together.”

True leadership is borne of service, not ambition. Mchunu, the former chairperson of the Inkatha Women’s Brigade, embodies this ideal. At 85, she remains a beacon of selflessness, a living rebuttal to today’s politics of greed.

The old proverb, ”Service is no heritage”, captures the fate of many struggle veterans. They served without expectation of reward, yet today’s leaders treat politics as a career path to wealth. As Hwa Yung wrote: “Leadership does not come from striving to be leaders but is the by-product of a life of humble service.”

We must purge the rot within our movements, not discard them entirely. The IFP, as Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi insisted, was always an extension of the ANC’s mission. Perhaps reuniting these strands, rooted in service rather than self-interest, is the way forward.

The departed heroes did not die for tenderpreneurs and Mercedes-Benzes. They fought for a just society. If we continue down this path, their spirits will indeed be broken.

* Dr Vusi Shongwe works in the Department of Sport, Arts, and Culture in KwaZulu-Natal and writes in his personal capacity.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, Independent Media or IOL.