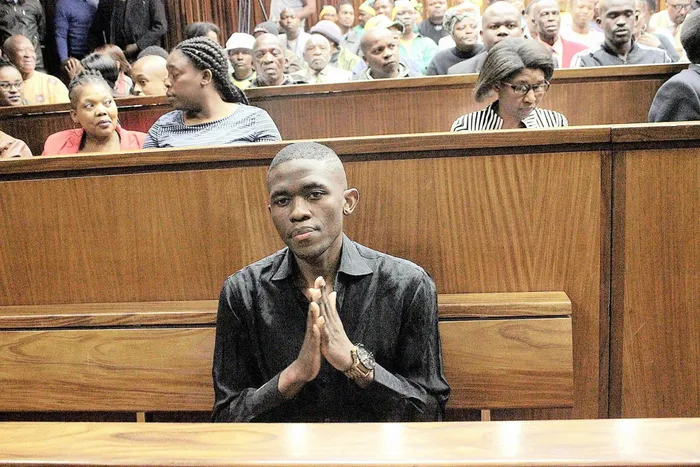

Convicted murderer Sandile Mantsoe. Convicted murderer Sandile Mantsoe.

The phenomenon of women being murdered by their intimate partners could be seen as a backlash, because patriarchy, or men’s power and control feel threatened by democracy.

This is the view of Mbuyiselo Botha, of the Commission for Gender Equality, following Sandile Mantsoe’s conviction and sentencing in the murder of his ex-girlfriend, Karabo Mokoena, last week. On the same day that Mantsoe was sentenced to 32 years in prison, another young woman, Zolile Khumalo, a student at the Mangosuthu University of Technology, was shot dead, allegedly by her boyfriend.

“How do you explain that? A young man who, unable to give up on a relationship, simply resorts to violence? That speaks to how men are socialised, that ‘if I can’t have you, no one will’,” says Botha, reflecting on Khumalo’s murder.

“Femicide is on the rise because some men feel that democracy has emasculated them.

“That in the 21st century men’s power feels so threatened that even students, whom you would ordinarily imagine are progressive thinkers, are feeling attacked.”

In the Johannesburg High Court on Thursday, the tension was palpable as Karabo’s family, seated in the public gallery, listened to evidence in mitigation of sentencing. The gallery erupted in ululation, and song when Judge Peet Johnson handed down a 32-year sentence.

In his verdict, the judge said the callous and meticulous way in which Mantsoe had covered his tracks proved he was a danger to society. “She was an abused woman. Abused women need to know they can be protected from the likes of you,” he said. “Karabo had a right to life, and you had no right to take it.”

Judge Johnson also said violence against women had become increasingly prevalent, despite harsher sentences. Mantsoe did not linger in the court room and seemed in a rush to leave the dock.

Karabo’s father, Thabang Mokoena, was visibly relieved. “The man thought he would get away with murder but he was caught and that’s it.

“Today I don’t accept his apology. I simply cannot promise I will ever accept it.”

Botha praised the judicial system. He said Mantsoe’s sentence was an example to other would-be perpetrators that South African society would not tolerate gender-based violence.

Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research associate Lisa Vetten questions why other forms of violence are also “incredibly high” in South Africa. “The high murder rate is a deeply entrenched problem,” she says, adding that the violence that men get exposed to from early childhood could be a factor contributing to this.

Vetten laments the shortage of essential infrastructure to help women who have been abused, saying that essential services for victims are inadequate. She explains that another reason for the country’s high levels of femicide is that the cycle of violence is not interrupted in families living under very difficult circumstances. “The problem is that we end up accepting and normalising violence. The children grow up with it, they experience it first-hand, they see it where they live and breathe, and what they learn is when life is difficult, when you are angry or upset, you respond violently.”

Botha and Vetten say better systems and services need to be put in place in terms of domestic violence and child abuse. “When a woman, either alone or with her children, has to escape violence, there must be a safe place to go, where the services provided are of a high standard.

“We need to train teachers, nurses, everyone across the board, about how to identify and respond when they identify this problem. It should also be something that’s taught at school, how to deal with conflict without having to be violent,” says Vetten. “We need to do early childhood intervention. Just imagine what could happen if, at an early age, boys were taught how to have a deep respect for the body of another person.

“When that boy goes to primary school and then secondary school, the message must be the same, it must become part of his intellectual DNA.”