New insights into Paranthropus robustus: a landmark study on human evolution

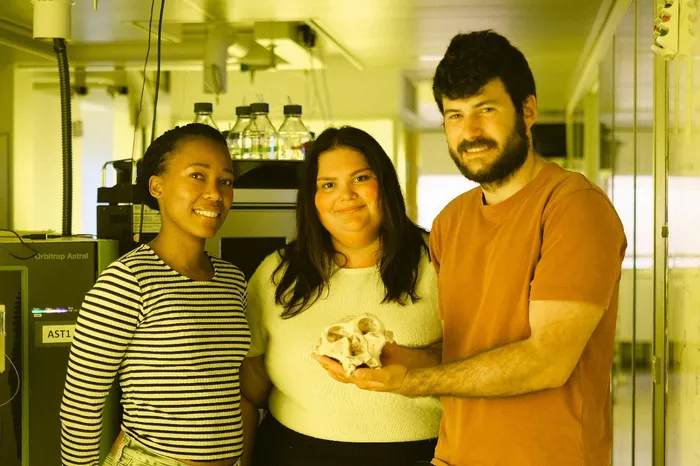

Dr Palesa Madupe, Dr Claire Koeng and Dr Ioannis Patramanis.

Image: Victor Yan Kin Lee

In a landmark study that pushes the boundaries of our understanding of human evolution, a research team led by scholars from the University of Cape Town (UCT) and the University of Copenhagen has unveiled powerful insights into Paranthropus robustus—a close, extinct cousin of modern humans.

Published in the prestigious journal Science, the study successfully harnesses two-million-year-old protein traces extracted from fossilised teeth, retrieved from the rich archaeological tapestry of South Africa’s Cradle of Humankind.

This pioneering research not only presents some of the oldest human genetic data ever recovered from Africa but also disrupts long-held beliefs about the biological make-up and diversity of one of our early hominin relatives. As Dr Palesa Madupe, co-lead of the study and a research associate at UCT’s Human Evolution Research Institute (HERI), explained: “By sampling multiple African Pleistocene hominin individuals classified within the same group, we’re now able to observe sexual dimorphism and genetic variations that existed among them.”

The central achievements of the study stem from advanced palaeoproteomic techniques and mass spectrometry, enabling researchers to identify sex-specific variants of amelogenin, a critical protein found in tooth enamel. Of the ancient individuals examined, two were confirmed as male, while innovative quantitative methodologies indicated that the others were female.

“Enamel is extremely valuable because it provides information both about biological sex and evolutionary relationships,” said Claire Koenig, co-lead and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Copenhagen’s Centre for Protein Research. “However, since identifying females relies on the absence of specific protein variants, it is crucial to rigorously control our methods to ensure confident results.”

Adding to the intrigue of this study, another enamel protein—enamelin—uncovered unexpected genetic diversity. While two individuals shared a particular protein variant, a third displayed distinct characteristics, and a fourth exhibited both, prompting co-lead Ioannis Patramanis to remark, “When studying proteins, specific mutations are thought to be characteristic of a species... we were surprised to discover that what we initially thought was a mutation uniquely describing Paranthropus robustus was actually variable within that group.”

This revelation necessitates a critical re-evaluation of how ancient hominin species are classified, illustrating that genetic variability—beyond mere skeletal features—must be integral to our understanding of their complexity.

“With this data, we shed light on how evolution worked in the deep past and how recovering these mutations might help us understand genetic differences we see today,”Dr Madupe said.

Living between 2.8 and 1.2 million years ago and walking upright, Paranthropus robustus likely coexisted with early members of the genus Homo. Although diverging on a different evolutionary path, their narrative remains crucial in chronicling the origins of modern humans.

This study marks a significant advancement in palaeoproteomics within Africa and underscores the critical role of African scholars in rewriting the story of human history.

“As a young African researcher, I’m honoured to have significantly contributed to such a high-impact publication as its co-lead. However, the journey towards inclusivity for researchers of colour continues, and more of us need to be leading research like this,” reflected Dr Madupe.

HERI at UCT is at the forefront of this transformative movement, having initiated innovative programmes that are imparting palaeoproteomic techniques to a new generation of African scientists, with a focus on expanding these training initiatives throughout the continent.

“We are excited about the capacity building that has come out of this collaboration. The future of African-led palaeoanthropology research is bright,” said Professor Rebecca Ackermann, co-director of HERI, as the team looks ahead to further discoveries that could reshape our understanding of human ancestry.

Related Topics: